Mindfull Meandering

Monday, December 29, 2025

Happy New Year 2026!

Wednesday, December 25, 2024

Happy New Year 2025!

2024 - 2023 - 2022 - 2021 - 2020 - 2019 - 2018

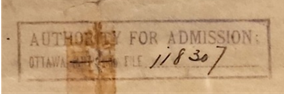

The Broitman Family Reunited

Introduction

Chaika Broitman and her three children were racing against time to leave Romania. Chaika’s husband Abram had make it to Canada in July 1924, successfully rescued from Europe by a Canadian refugee resettlement program. Unfortunately, that program was already experiencing problems in the summer of 1924, and in October new limitations were enacted that all but barred Russian Jewish refugees from entering Canada.

According to a letter from JDC Acting Chairman Dr. B. Kahn to his American colleagues, dated July 30, 1924 , conditions in Romania were getting increasingly desperate. Two thousand and sixty refugees remained in Bucharest, with 80% of them already having been stuck there for three or four years. This was likely true of the Broitmans, who had spent time in both Kishinev and Bucharest. Dr. Kahn further noted that one-third of the refugees were “…beggers, cripples, insane people, people who are unfit of the work, [and] deserted wives.” He bemoaned the limitations of the Canadian refugee program, and accused the ICA of only supporting those refugees with the financial wherewithal to defray some of the costs of their travel. He concluded his letter by saying, “we are unable to tell what will happen to [the refugees] after [November 1, 2024].”

The Broitmans were fortunate: they were selected to leave that November on what would be the program’s very last transport of Russian Jewish refugees out of Romania. Had they not left then, it is not clear what would have happened to them.

|

| Front of the 1924 Passport of Chaika Broitman and her three children. |

A Story in Stamps

When Rose Broitman Telles moved out of her home in New Jersey and into a nursing facility around 2002, I was the one who went through the papers in the cabinet in her guest room. Among the treasures I found was an enigmatic passport dated 1924, with Chaika’s name and the names of the three children. With information in both French and Russian, I had no idea at the time what stories it would tell. Professor Rodica Botoman at The Ohio State University kindly helped me understand the meaning of the various stamps. Understanding the importance of the document, I had it professionally preserved, deacidifying the paper and removing any adhesive tape.

The passport includes the vital information in French (shown) and in Russian on a second page. It was issued by the Russian consulate in Bucharest; but it is important to remember that there was actually no country called “Russia” at the time. The Soviet Union had been established, but Romania had not yet recognized that government. In the meantime, representatives of the previous government remained at what had been the Russian consulate to manage any state property and to help displaced Russian citizens.

A single passport was issued on September 19, 1924, to Chaika and her three minor children. Boys were listed on the left side, and girls on the right. Rose’s age is listed as four, but according to family stories, she was actually five or six. She was small for her age, probably due to years of malnutrition. The passport lists Chaika’s last place of residence in Russia as Savran in Podolia.

The administrative hurdles that would allow Chaika and her children to leave Romania for Canada were daunting. Permission for travel required the approval of Russian, Romanian, and Canadian officials, plus visas from any country through which the refugees would pass. Undoubtedly, these approvals were facilitated by representatives of ICA, JDC, and HIAS in Romania. The refugees travelled as a group of 500, by train, and the route they took was part of the famed Orient Express.

By the time Chaika reached Halifax weeks later, her family passport included sixteen stamps in seven languages. The passport tells the story of their journey.

|

| Advertisement for the Simplon Orient Express. The route taken by the refugees, which followed one of the routes of the Orient Express, was the most direct train route from Bucharest to Trieste at the time. |

|

Passport |

Language |

Location |

Date |

Translation/Meaning |

|

|

N/A |

Bucharest Romania |

Sept. 1924 |

This haunting photo of Chaika and her children is the oldest photo we

have of the family. They are all wearing simple clothing. Chaika, who was

described as full-figured when she was older, looks absolutely gaunt. There are no signs of a stamp because this was not the original

passport photo, though it was found with the passport in 2002. The original photo must have fallen off

decades earlier. |

|

|

Russian |

Bucharest Romania |

Sept. 19,

1924 |

These stamps from the Russian consulate confirm the authenticity of

the (original) photo, the signatures, and the 200 lei payment (worth approximately $1 USD in

1924). |

|

English |

Bucharest Romania |

Sept. 26,

1924 |

A week after obtaining their passport, the Broitmans received

approval from the Canadian consulate allowing entry into Canada. |

|

|

|

English |

Bucharest Romania |

Sept. 26,

1924 |

This stamp is located on the back of the passport. According to a

representative from the Pier21 Canadian Immigration Museum, “…this

handwritten completion of a stamp appears to be for a (successful) overseas

inspection on 26 September 1924. The timing and potential to be assigned a

"category" suggests that this is the stamp for the overseas

medical examination. The signature is likely that of an authorized doctor

overseas.” The barely legible third line might read “Port: Bucharest.” |

|

|

French |

Bucharest Romania |

Oct. 28, 1924 |

To get from Bucharest to the port in Trieste, the Broitmans would need to travel through the “Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.” This country, which was formed in the aftermath of WWI, would be renamed Yugoslavia in 1929. Nearly a month after getting their stamp from the Canadian government, Chaika received approval to pass through the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes en route to Italy. The family wasted no time leaving Bucharest, their home for the past

several years. They rushed to the border, covering almost 400 miles in the

next 72 hours. |

|

|

Romanian |

Jimbolia Romania |

Oct. 31, 1924 |

This stamp indicates the departure of the Broitmans from Romanian

territory. The town name isn’t completely clear, but based on their entry

point into the future Yugoslavia, they must have crossed the border at

Jimbolia -- almost 400 miles from Bucharest. |

|

Serbian |

Kikinda

(Кикинда) Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (now Serbia) |

Nov. 1, 1924 |

This stamp indicates their entry into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (Краљевина Срба, Хрвата и Словенаца). The entry point was Kikinda in modern-day Serbia, right on the border with Romania and less than 15 miles from Jimbolia. |

|

|

|

Serbian |

Rakek

(Ракек) Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (now

Slovenia) |

Nov. 3, 1924 |

Two days after entering the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes at

Kikinda, the family crossed the border into Italy at what is now Rakek,

Slovenia. The journey from Kikinda to Rakek was another 400 miles. |

|

|

Bosnian/

Croatian |

Unknown |

Unknown |

This stamp means “no holding back,” presumably indicating that the

family passed inspection. It is unclear if this occurred when they received

their visa; upon entry into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes; or

days later, somewhere in the interior of the country. |

|

Italian |

Postumia Italy (now

Slovenia) |

Nov. 3, 1924 |

Rakek is only seven miles from Postumia, which in 1924 was part of

Italy. Postumia is 30 miles from Trieste. |

|

|

Italian |

Trieste Italy |

Nov. 5, 1924 |

Two days after arriving in Italy, the Broitmans left for Canada at

the Port of Trieste. They had traveled more than 850 miles in 4-5 days. The overland portion of their journey was complete. |

The Port of Trieste

|

| Undated photo of the port of Trieste. |

The Broitmans stayed in the Italian port city of Trieste for only a few days, and little is known about their time there. They were likely confined to a boarding house to ensure they continued to their destination. A committee supporting the Jewish migrants and refugees had been established in Trieste after WWI. Called the “Comitato di assistenza per gli emigrati ebrei,” it was in operation until 1943. Perhaps they helped the Broitman family and their fellow refugees.

|

| Plaque commemorating the work of the "Comitato di assistenza per gli emigrati ebrei" (Committee for the Assistance of Jewish Emigrants) in Trieste. The text reads: "The Italian committee for assistance to Jewish emigrants had its headquarters and operated here from 1921 to 1943. They organized the aliyah [calling up] to Israel of the Jews from Central and Eastern Europe. In this building they found hospitality and rest while waiting for the embarkation to the promised land. Trieste deserves the name of "Gate of Zion." Posted on the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the State of Israel." Photo courtesy of Professor Aleksej Kalc of the Slovenian Migration Institute. |

The SS Presidente Wilson and Family Stories Confirmed

|

| Undated postcard of the Presidente Wilson. "T.S.S." indicates "Turbine Steam Ship" |

My grandmother, Rose Broitman Telles, told me stories about her voyage on the ship. Only five or six years old or so at the time, she remembered sneaking out of steerage into first class to collect oranges for her pregnant mother. Another story she told was of a giant wave hitting the ship in the middle of the night, causing 13-year-old brother Aron to fall out of his bunk. An archivist in Halifax kindly shared newspaper account confirming that the SS Presidente Wilson was in fact hit by a rogue wave.

Arrival

On November 20, 1924, almost a month after leaving Bucharest, Chaika and her family made it to Halifax. Their processing there was likely similar to that of Abram just a few months earlier.

Stamps on the back of their passport tell of the next part of their journey.

|

Language |

Location |

Date |

Translation/Meaning |

|

|

|

English |

Halifax, Nova

Scotia, Canada |

Nov. 20, 1924 |

This stamp indicates

arrival into Canada, and overlaps with the health inspection stamp made two

months previously. According to representatives from the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier21, GLM likely corresponded

to the inspecting officer. |

|

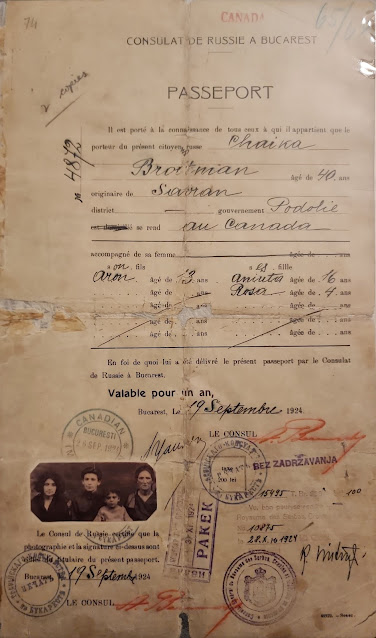

|

English |

Halifax, Nova

Scotia, Canada |

|

The

"authority for admission" file indicates an administrative file related

to admission. This was likely created in response to correspondence between

the settlement agency (JCA) and the immigration branch (Ottawa) to assist a

group of immigrants in entering the country. |

Having jumped through all the immigration hoops, Chaika and her family boarded a train to Toronto, where she was reunited with Abram. They hadn’t seen each other in almost five months. Abram’s address on the “Report of the distribution of the Twelfth group of 511 refugees was listed as 29 Kensington Avenue. Two months after reaching Canada, on January 25, 1925, Chaika gave birth to their son Joseph. After five years and nearly 6,500 miles, the Broitmans’ long journey from the horrors of the revolutionary pogroms to the safety of the West was over.

Next…new beginnings.

|

| Interwar map of Europe with Yiddish place names. The path taken by the Broitman family is indicated in red. |

|

| Record of the Broitman family's arrival in the Canadian Jewish Archives |

Monday, November 25, 2024

The Refugee Program Unravels

Abram Broitman told refugee program officials that he was single, but in truth he’d been married for at least 12 years. When he left Bucharest for Canada in July 1924, he left behind his wife, Chaika, and their three surviving children -- Anita, Aron, and Rosa – with another child expected in January. While Abram began establishing a new life in Toronto, his family was preparing to join him, and none too soon: ultimately, Chaika and their children would be among the very last refugees allowed into Canada through the program.

Refugee Program Recap and Context

The unrest of the Ukrainian War of Independence and the violent pogroms between 1917 and 1920 led tens of thousands of Jews who had been living in what is now Ukraine – and was then part of Russia – to flee to Romania, Poland, and Constantinople in Turkey. These Russian-Jewish refugees were stateless: the new Soviet government refused to repatriate them, and their new “host” countries were unwilling to absorb them or even integrate them into existing Jewish populations.

In Romania, tolerance of these refugees was particularly low. In 1921 the Romanian government declared its intention to expel the Russian-Jewish refugees – which is to say, to push them back to the Dniester River at the Soviet border, where they would have been shot by soldiers or drowned. Pressure from the League of Nations and other groups led to the repeal of the edict, but in 1923 Romania announced that the Russian-Jewish refugees had to leave by October of that year. Additional international pressure softened this deadline as well, but the writing was on the wall. The refugees could not return to their homes in Russia, could not stay in Romania, and had nowhere to go.

|

| "Children rescued by JDC from the famine area of Bessarabia arrive in Bucharest." 1929. JDC Archive # 11980; NY_00947 |

A refugee resettlement program was established to rescue these Jews. The program never really had a name; in the relevant documents, there are only references to “the refugee situation,” “Russo-Rumanian Refugees,” the "ICA Quota," "the ICA agreement with the Canadian Government," and a Canadian "concession...to set aside the Immigration Law." The overall program was responsible for resettling refugees in Argentina, Palestine, and the United States, but this blog post focuses on the Canadian arm of the program. For the purposes of this post, then, I will refer to the Canadian part of the Russo-Romanian refugee resettlement program simply as “the program.”

America, long the refugees’ preferred safe harbor, had established immigration quotas in 1923 and was set to make them even more restrictive in 1924. The Canadian government was less xenophobic than their American neighbor to the south, but only slightly: in addition to requiring that new immigrants to Canada be of sound mind, in good health, and financially self-sufficient, the Canadian Immigration Act of 1919 severely restricted the admission of individuals who had "peculiar customs, habits, modes of life and methods of holding property” that were not aligned with Canadian values. Individuals from specific countries, including Russia, were therefore to be denied entry because those individuals might have “dangerous ideologies” that could infect Canadian society. Between the American quotas and the Canadian restrictions, the 1920’s saw a marked decline in Jewish immigration to North America from Eastern European countries.

The Canadian chapter of the Jewish Colonization Association, chaired by one Mr. Lyon Cohen, stepped up to help their Russian co-religionists. They appealed to the Canadian Dominion government’s Minister of Immigration, the Honorable J.A. Robb, and his deputy, Mr. W. J. Egan, to allow the entry from Romania of as many stateless Russian-Jewish refugees as possible.

Mr. Robb approved this new program in October 1923 and agreed to issue 5,000 visas to the Russian-Jewish refugees in Romania. However, there were a few stipulations:

- The refugees needed to demonstrate that they had sufficient financial resources that they wouldn’t become a burden on the state. (If they were unable to, the Jewish philanthropic organizations facilitating refugee resettlement had to raise the funds to support them.)

- A portion of the refugees needed to settle in the prairie provinces and work as farmers.

- A “fair share” of the refugees needed to be transported on Canadian-flagged ships.

Between November 1923 and October 1924, thanks to the efforts of the ICA, JDC, JCA-Canada, and HIAS, some 2,500 Russian-Jewish refugees were successfully relocated from Romania to cities and farms across Canada. According to JCA annual reports, the number of stateless Russian-Jewish refugees in Romania dropped from 45,000 in 1922 to 13,000 in 1923, and was down to just 1,500 in 1924. Only a fraction of these individuals had gone to Canada; the rest had found their way to other countries that would accept them. By the summer of 1924, there were so few refugees left in Romania that on July 31, the Central Relief committee of the JDC closed its office in Bucharest. It was left to the local representatives of the program to get the last 1,500 refugees onto ships out of Europe.

In the meantime, although almost all the Russo-Jewish refugees in Romania had been successfully rescued, there were still thousands of stateless Jews stuck at ports across Europe. Many of them held valid visas for entry into the United States, and had already made their way overland to European ports on their way to America, when draconian changes to US immigration policy effectively closed American borders – even to those individuals with valid entry visas. Some even made it all the way to American waters, only to be denied entry and turned back to Europe because the new immigration quotas had already been filled.

Thus, thousands of stateless Russian Jewish refugees wound up stranded in European ports. They could not return to their country of origin (Russia,) and they were unwelcome in the intermediate countries (Romania, Poland, and Turkey) where they had been refugees during their journey to the ports. Even their movements in the port countries (primarily France, Germany, and England) were severely restricted.

The JDC and the JCA lobbied for the remaining 2,000 Canadian visas to be issued to the Jewish refugees stranded at the ports. After all, they were exactly the type of refugees that the program had been designed to help.

But the Canadian authorities disagreed. In September of 1924, Mr. Robb announced that, going forward, all Jewish immigrants would have to qualify as agricultural workers, with “reasonable assurance that they intend to remain on farms” -- a move that effectively barred Russian Jews from entering Canada. A newspaper article about this new policy, published in the Ontario-based Brantford Expositor on September 13, 1924, was titled “Toronto Jews See Tragedy in Immigration Ruling.”

In a letter dated October 20, 1924, Mr. Egan wrote the following to the JCA in Paris:

“[Y]ou still are of the opinion that the Russians at the various ports are refugees in every sense of the word. That is the difficulty between us. We tell you why we granted a quota of 5,000, and the type of Russian Jewish refugee that comes under same, but you insisted that your refugee is equally admissible, and we say no. That is why I say that we are administering the law as far as entrance into Canada is concerned, and not on your decision as to what a refugee is or may be.” (Dworkin Archive: 1924_10_20 ICA-S-CB-3)

The remaining 2,000 visas were never issued, and the Canadian program was officially closed.

Possible Causes for Cancellation

It seems safe to assume that the program wasn’t cancelled over a disagreement about who counted as a refugee. It had originally been launched with three stipulations: that the refugees not be financially reliant on the Canadian government, that they work primarily as farmers, and that they sail on Canadian ships. Were these conditions met?

Financial Matters and Inter-Organizational Disputes

The first condition for the entry into Canada of 5,000 refugees was that they not become a burden on the state. In practice, this meant that Jewish organizations needed to support the refugees until they could support themselves. The program was cobbled together at a time before there were any formal structures for supporting refugees, and none of the governments involved – Canadian, American, Soviet, or Romanian – provided financial resources to support refugee resettlement. A full review of the costs of the project is impossible to reconstruct, but correspondence in the JDC and JCA archives makes this much clear: whatever funds were raised were insufficient to the need.

Early on, the Canadian JCA appealed to American philanthropic organizations to support refugee resettlement efforts in Canada. The Canadian JCA had a message for the Americans, and it was this: If your government hadn’t shut its borders, these refugees would be coming to you, and you would be financially responsible for them. But since the refugees are coming to us, and we have far fewer financial resources than you do, it is your ethical duty to help us defray the cost of absorbing them.

While the Canadian JCA did indeed receive funds from American groups, in practice, the task of supporting individual families often fell to local communities. There is no evidence that the Canadian Dominion government felt that the refugees lacked sufficient support once they were in-country, so this may not have been a major factor in the decision to end the program; but it certainly led to considerable stress across the Canadian Jewish world.

To Farm or Not to Farm

Another stipulation of the Canadian program was that a portion of the refugees be sent to JCA agricultural colonies in the prairie provinces. But correspondence between Canadian JCA representatives in the summer of 1924 – as Abram Broitman was about to arrive – revealed that this proved impossible. Try as the JCA might, they were unable to turn the new arrivals into farmhands. The fact was that the refugees, who were physically very frail and had no agricultural experience, were simply not well suited for farm work. Even the JCA’s own Jewish-led colonies turned most of them away.

Mr. Robb justified the decision to suspend the remaining 2,000 visas in part by pointing to Canada’s need for new farm workers, a need that was clearly not being met by the Russian Jewish refugees. But was this the true reason? After all, Canada really had needed farm workers when the program was established in 1923; but in 1924, a drought in the west meant that there was limited need for farm workers of any nationality. Was the farming issue merely a pretext for anti-Jewish legislation?

Canadian authorities insisted that their decision to cancel the remaining 2,000 visas was not an anti-Jewish act. Indeed, in a letter to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency dated October 27, 1924, a Canadian immigration official declared that “Canada does not say, to use the phrase employed on the subject of the United States, that she prefers persons belonging to the Nordic race.” Less than two months later, though, Mr. Robb admitted that “the immigration of Northern Europeans is the chief objective of the new policy.”

Steamship Troubles

The original deal between the JCA and the Canadian government called for Canadian-flagged steamships to be used to transport the refugees. However, the JCA did not honor this stipulation. Of the eleven ships that carried refugees to Canada, only the first three were Canadian-flagged. The reason: the Paris-based ICA – an organization independent of the Canadian JCA – had struck a deal with a French shipping line, the Fabre Line, which offered deeply discounted fares in exchange for the ICA’s business. Given the enormous sums of money being spent to help the waiting refugees in Romania, evacuate them from Europe, and then support them in their new countries, the JCA couldn’t afford to turn down the deal.

Unfortunately, this decision had ripple effects back in Canada. On August 18, 1924, a meeting was convened in Ottawa at which representatives of the Dominion government, the JCA, and the Canadian steamship companies met to discuss why refugees had arrived on European-flagged ships. (Dworkin Archive 1924_08_22 ICA-S-CB-18-1924). The Canadian shipping line representatives did not believe they were receiving their “fair share” of passengers, and were thus losing out on considerable potential income.

|

Ship Name |

Line |

Dates |

Ports of Departure |

Port of Arrival |

|

SS Montclaire |

Canadian

Pacific |

16 Nov 1923 |

Antwerp,

Belgium & Southampton, UK |

Saint John,

NB |

|

SS Melita |

Canadian

Pacific |

2 Dec 1923 -

11 Dec 1923 |

Antwerp,

Belgium & Southampton, UK |

Saint John,

NB |

|

SS Minnedosa |

Canadian

Pacific |

24 Dec 1923 |

Antwerp,

Belgium & Southampton, UK |

Saint John,

NB |

|

SS Canada |

Fabre Line |

8 Dec 1923 -

Jan 1924 |

Constanța,

Romania |

Halifax, NS |

|

SS Asia |

Fabre Line |

16 Jan 1924 -

Feb 1924 |

Constanța,

Romania |

Halifax, NS |

|

SS Braga |

Fabre Line |

16 Mar 1924 -

Apr 1924 |

Constanța,

Romania |

Halifax, NS |

|

SS Madonna |

Fabre Line |

26 Apr 1924 -

29 May 1924 |

Constanța,

Romania |

Halifax, NS |

|

SS Asia |

Fabre Line |

7 Jul 1924 -

31 July 1924 |

Constanța,

Romania |

Halifax, NS |

|

SS Madonna |

Fabre Line |

9 Aug 1924 -

29 Aug 1924 |

Constanța,

Romania |

Halifax, NS |

|

SS Braga |

Fabre Line |

7 Sep 1924 -

30 Sep 1924 |

Constanța,

Romania |

Halifax, NS |

|

SS Presidente Wilson |

Austro-Americana

Line |

5 Nov 1924 -

20 Nov 1924 |

Trieste,

Italy |

Halifax, NS |

Table listing the ships involved in the Program, as reconstructed through review of "Canada, Ocean Arrivals (Form 30A), 1919-1924" database at Ancestry.com. Internal documents indicate that the Presidente Wilson was the 12th ship in the program, but I was only able to find 11 major groups.

“[T]he balance of the Russian Jewish refugees’ movement was granted with the distinct understanding that if we included refugees on the continent but outside of Romania, a fair share of the business would be given to the Canadian lines. Unless this is adhered to, the ICA Quota will be strictly confined to Russian Jewish refugees now in Romania and visas will be granted only in Bucharest.” Dworkin 1924_08_01 ICA-S-CB-3

The Bolshevik Scare and Potential American Resistance

We have discussed the original three stipulations of the program; but a fourth factor likely carried the most weight in the decision to cancel it. It was the rise of the new Communist regime in the Soviet Union, and the accompanying “Bolshevik scare,” that had led to the restrictive Johnson-Reed Act in the US. Of course, this affected Canadian politics as well. The JCA actually had to reassure the Canadian government that the refugees fleeing persecution at the hands of the Bolsheviks were not themselves Bolsheviks. In a letter dated June 5, 1924, a JCA representative wrote to Mr. Egan and Mr. Robb, “We wish further to assure you that we have no desire to assist in any manner, Bolshevists to come to this country.” Dworkin 1924_06_05 ICA-S-CB-3

It is likely – although there is no documentation to positively substantiate it – that American authorities were quite unhappy that the Canadian government was considering admitting the Jews stuck in the European ports. An article published in the Jewish Daily Bulletin on November 13, 1924, quoted Mr. Egan as saying that "The Canadian Government had a gentleman’s agreement with Washington to which it desired to live up to, that Canada should not admit immigrants who held American visas." Many of those individuals had been bound for the US and did hold valid American entry visas, and America was worried that allowing them into Canada would only make it easier for them to enter the States. Deputy Egan was clear about the American position. He stated that “our neighbor south of the boundary would seriously protest against using Canada as a back door for the United States admitting into Canada those who could not enter the United States on account of the recent legislation.” This American pressure doubtless contributed to Canada’s decision to discontinue the program.

Conclusions

Anti-immigrant, anti-Communist, and general anti-Jewish sentiment, as well as American pressure, probably all played a role in the cancellation of the program, and the JCA’s decision not to give their business to the Canadian steamship companies did not help matters. The failure of the refugees to become farmers, and the fact that most of them consequently did not settle in the prairie provinces, provided convenient, and perhaps reasonable, justification for the withdrawal of the remaining 2,000 visas. Whatever the reasons, the end result was that the program was shut down and the flow of Russian-Jewish refugees to Canada was stopped.

An article in the Jewish Daily Bulletin dated November 13, 1924, titled “Blame Paris ICA for Canadian Government’s Cancellation of Agreement” noted that “2,500 refugees have already come into Canada with the help of the Paris ICA, and 496 are now on the high seas from Trieste to arrive in Canada at the end of November.” They were referring to the SS Presidente Wilson, which had set sail on November 5, 1924. It was the program’s last ship to leave Europe. Chaika, Anita, Aron, and Rosa Broitman were on board.